People handle adversity differently; some break down sooner than others. When a team focused on a common goal faces adverse conditions, dissent among some team members precludes them from reaching a shared goal. Under extreme conditions, a mutiny isn’t just mission-critical—it can leave everybody dead. The famous explorer Ernest Shackleton, best remembered for his Antarctic expedition of 1914–1916 in the ship Endurance, managed such risks by assigning the whiny, complaining crew members to sleep in his own tent and share the chores with him. Clustering the “complainers” with him minimized their negative influence on others, and this helped his team survive and accomplish their goals.

Medicare Vs. Private Payers

It’s essential to acknowledge the contrasting dynamics between Medicare and private payers. Medicare, as a government-backed program, follows distinct regulations and reimbursement structures, while private payers operate in a competitive market with more flexible terms. The negotiation strategies and considerations may differ significantly when dealing with these two payer types.

Payment negotiations

Actively negotiating with payers is crucial for independent medical practices. However, many providers lack experience or haven’t been successful in past negotiations due to inadequate preparation. To ensure a fruitful negotiation, it’s vital to:

- Know Your Data: Understand your practice-specific data, including patient volume, charges, reimbursement history, and more.

- Know the Terms of Each Contract: Familiarize yourself with your current payer-specific contract terms, especially the reimbursement schedule and the claims filing data. (Babcock, 2021)

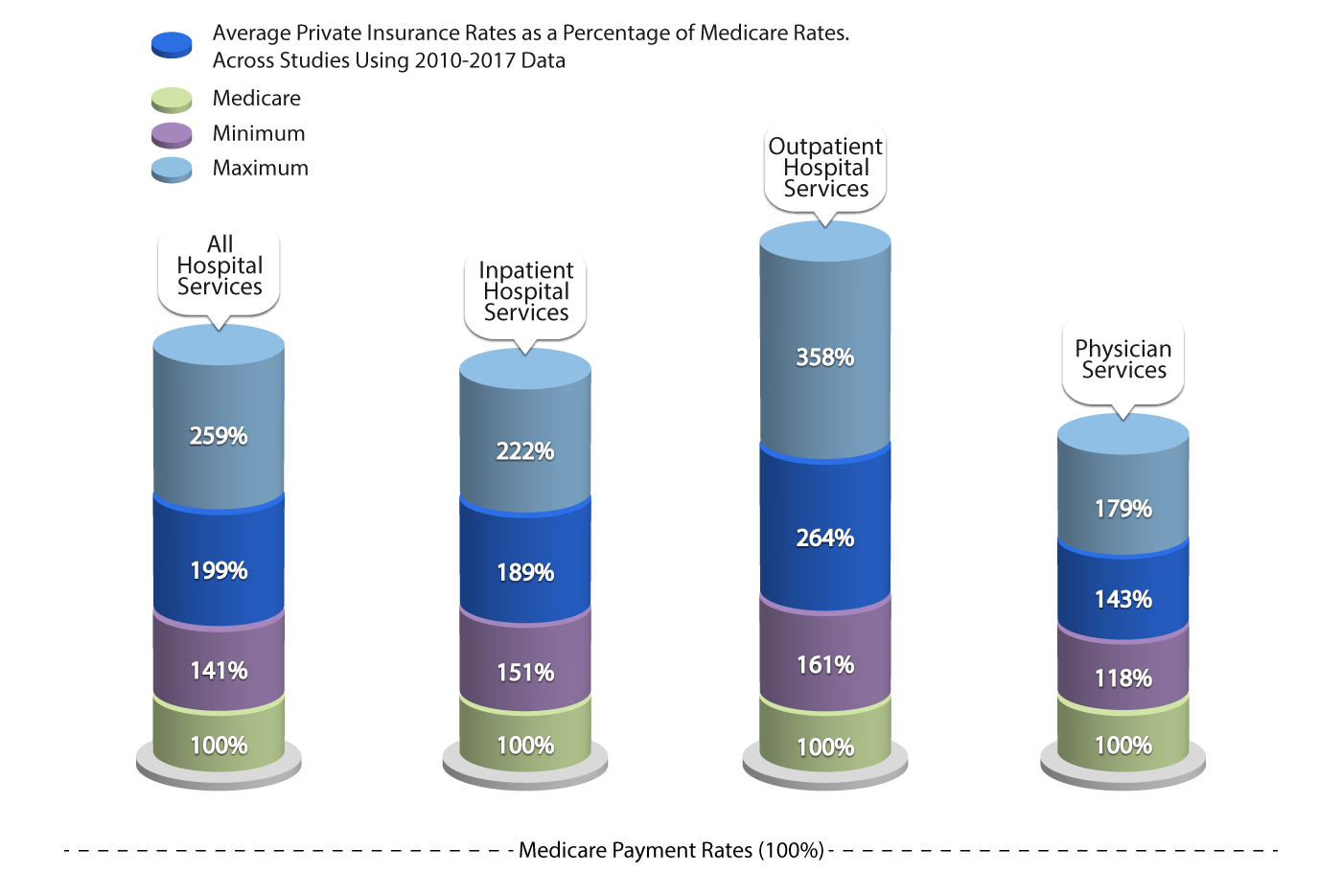

According to a KFF analysis, as seen in the image below, private insurers often pay nearly double the Medicare rates for hospital services. Specifically, for outpatient hospital services, private insurance rates were found to be significantly higher than Medicare rates, averaging 264% of the latter. This difference underscores the varying dynamics and market powers between Medicare and private insurers. Policymakers and analysts continue to debate the necessity of high payments from private payers to compensate for the lower Medicare payments. (How Much More Than Medicare Do Private Insurers Pay? A Review of the Literature | KFF, 2020)

Classification of Payment Models

Payment models dictate how healthcare providers, including physicians and hospitals, are remunerated for their services. Each model inherently carries incentives and disincentives that can influence the balance between cost reduction and improving care quality. These two objectives often stand at odds. This report delves into the implications of Alternative Payment Models (APMs) in either mitigating or intensifying health disparities. However, before exploring these implications, it’s essential to understand the incentives and disincentives embedded within the prevailing payment models. These incentives play a pivotal role in fostering cost-efficient, high-quality care.

The primary distinction among these payment methods lies in the unit of payment. This determines how financial risk is distributed between the payer and the provider. The nature of this risk can significantly influence the behavior of healthcare providers and the overall efficiency and effectiveness of the healthcare system (Quinn, 2015).

Factors affecting payment negotiations

According to AMA, it’s not just about the rates but also about the terms and conditions that can impact payment. For instance, some contracts might have clauses that allow payers to change rates without notice, or they might have stringent requirements for prior authorizations. Providers should be wary of “most favored nation” clauses, which can restrict them from offering better rates to other payers. It’s also crucial to be aware of the dispute resolution process outlined in the contract, should any disagreements arise. By being well-prepared and understanding the intricacies of payer contracts, providers can position themselves for more favorable negotiations and better financial outcomes. (American Medical Association & American Medical Association, 2022)

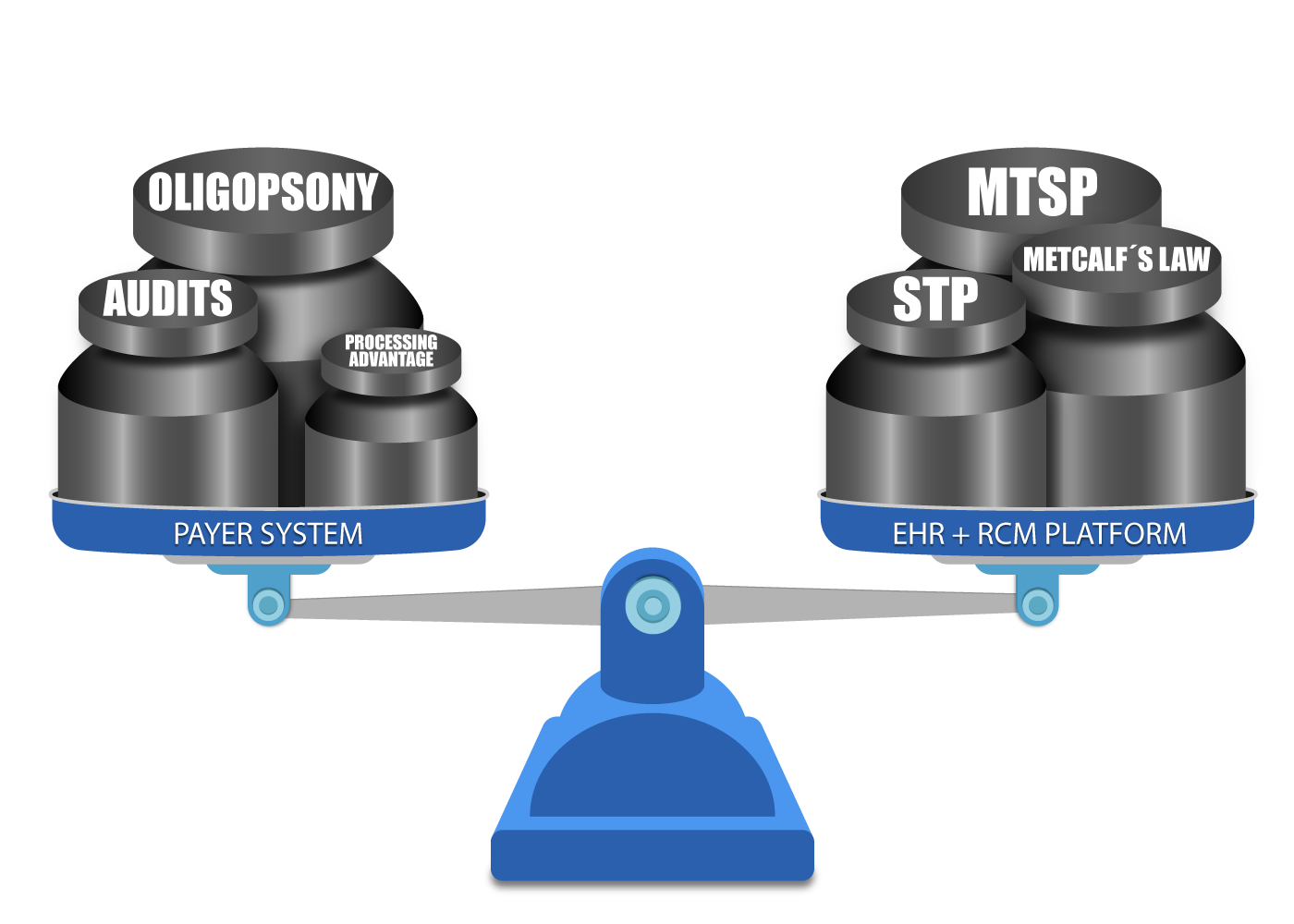

Payer-provider conflict

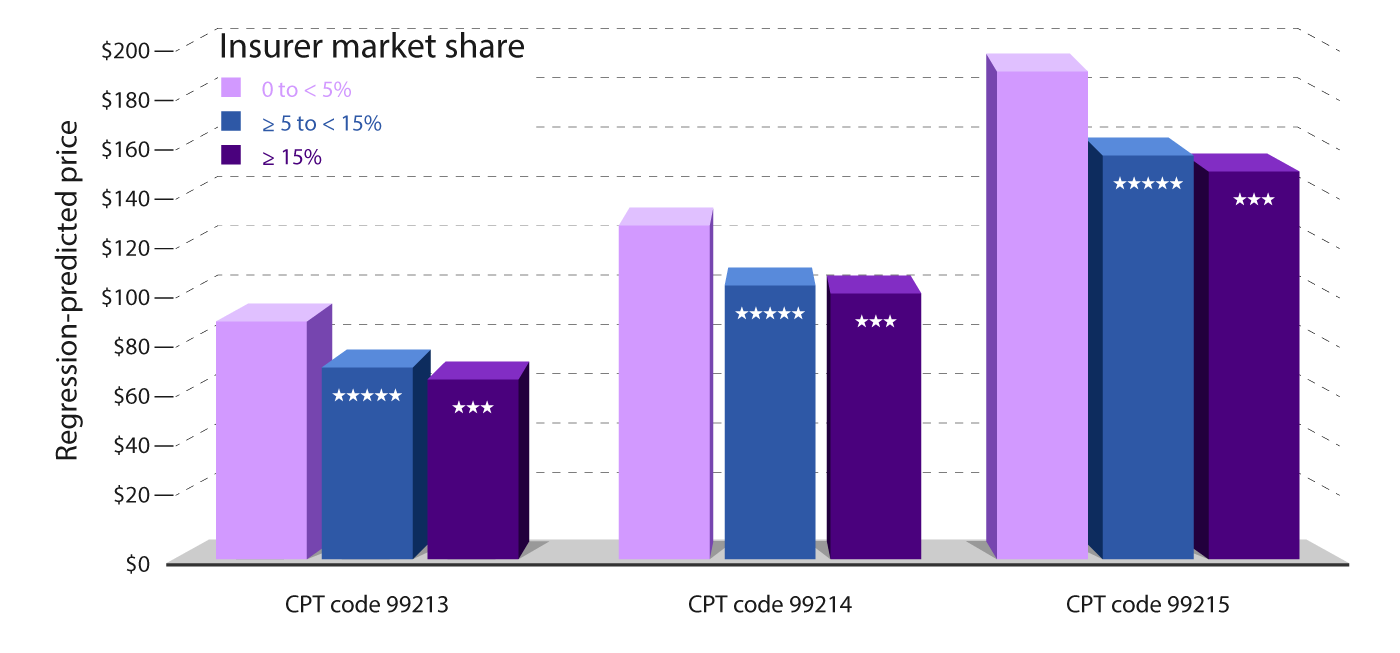

In the payer-provider conflict, the providers who accept lower reimbursement and who don’t challenge underpayments or delayed payments make it easier for the payers to maintain their market control (oligopsony). Recent research supports this notion, indicating that payers with larger market shares have more negotiating power in contract negotiations (HealthPayer Intelligence).

ClinicMind’s network helps providers maintain their payment schedules and motivation by establishing a shared discipline for clients and billers alike in terms of both thought and action.

Payers with Larger Market Share and Their Negotiating Power

Payers that have a dominant presence in the local market have a distinct advantage when it comes to negotiating lower prices for physician office visits. A study conducted by researchers from Harvard Medical School found that health insurance companies with a market share of 15% or more negotiated visit prices that were 21% lower than those set by payers with a market share of 5% or less. For instance, payers with less than 5% of the market negotiated prices of $88 per office visit. In contrast, those with 5 to 15% of the market share settled for a price of $72, and those with more than 15% of the market share negotiated even lower at $70 per visit. The graph below shows this analysis.

From Policy Changes to Physician Consolidation

In 2010, President Barack Obama signed the Affordable Care Act (ACA) into law, a move that expanded Medicare’s reach by adding millions to its coverage. This expansion meant that more physicians had to accept Medicare rates, which have been systematically reduced over time. The ACA not only aimed to extend healthcare access to uninsured Americans but also set in motion a wave of consolidation in healthcare services.

As Medicare adjusted its rates, private insurance companies followed suit. While they still paid above Medicare rates, they too began to reduce their payouts. This trend forced physicians to grapple with a challenging reality: working more hours for less pay.

The Power of the Network Effect

In response to these financial pressures, physicians began to see the value in consolidating their practices. By joining larger organizations, they could harness the network effect, gaining more significant negotiating leverage with insurance companies. This consolidation is not just about survival; it’s about strength in numbers. Large groups, especially those with revenues exceeding $1 million annually, have more room to negotiate than smaller entities.

The Rise of Management Service Organizations (MSO)

Amidst these challenges, the MSO model emerged as a beacon for physicians seeking to modernize while retaining their independence. Backed by private equity, MSOs offer economies of scale, growth opportunities, and, in some cases, increased reimbursement rates. They present a win-win, allowing physicians to remain autonomous while benefiting from the resources and expertise of a larger organization.

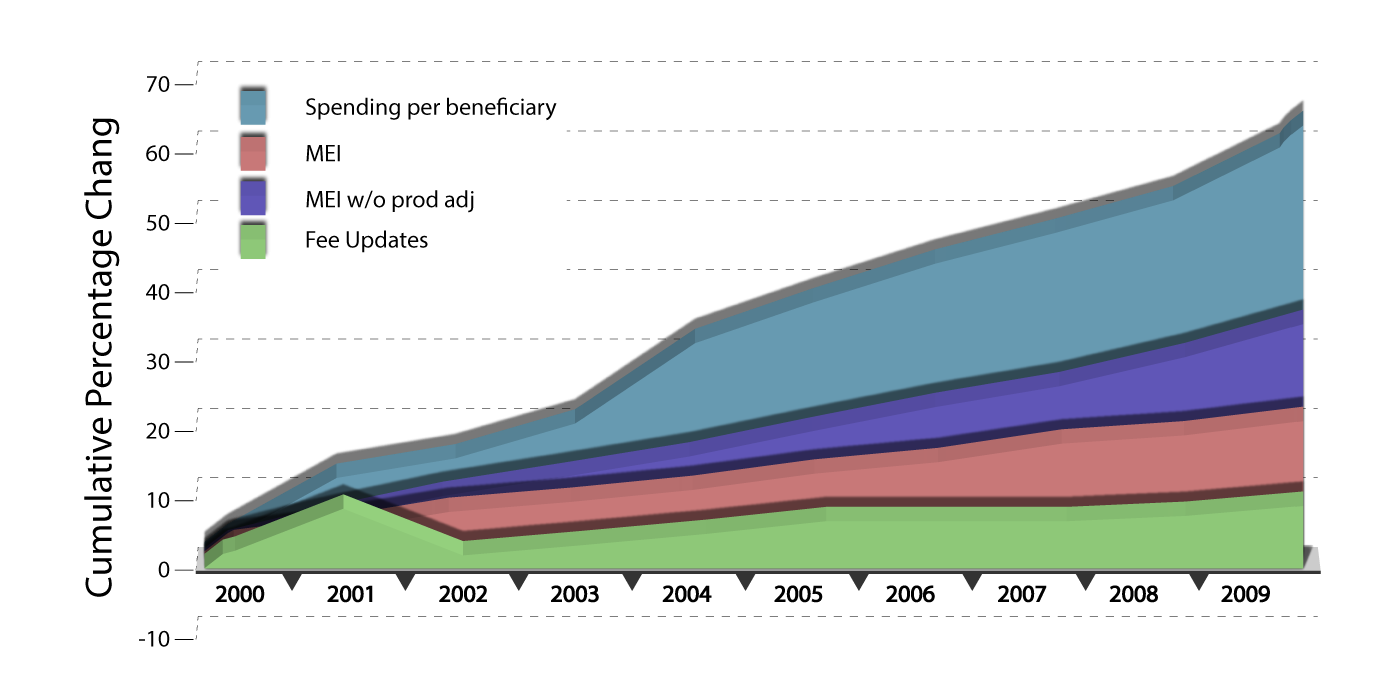

Despite Medicare’s conservative fee updates, total Medicare spending on physician services per beneficiary grew by 60 percent from 2000 to 2009. This growth rate, averaging 5.4 percent annually, underscores the influence Medicare has on the broader healthcare landscape, prompting private insurers to recalibrate their payment structures. (Frakt & Frakt, 2014)

Physician Burnout and Time Allocation

A significant concern in the medical community is the increasing administrative burden on physicians. Reports suggest that doctors spend 27% of their time in their offices seeing patients and a staggering 49.2% on paperwork. This administrative overhead, coupled with reduced reimbursements, contributes to physician burnout and challenges in patient care.

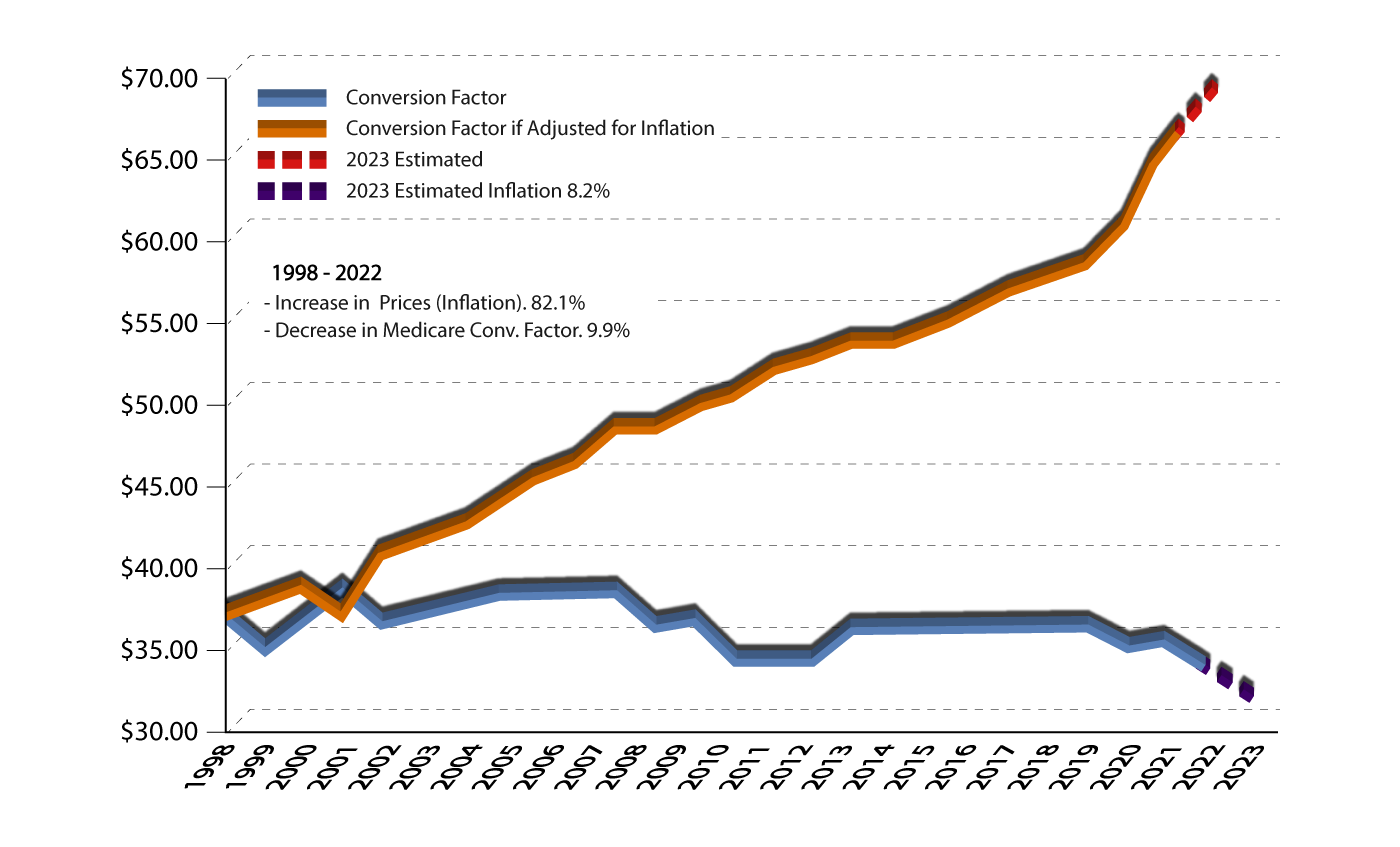

The Medicare conversion factor (CF) is a scaling factor that converts the geographically adjusted number of relative value units (RVUs) for each service in the Medicare physician payment schedule (MFS) into a dollar payment amount. The initial Medicare CF was set at $31.001 in 1992. Until 2015, subsequent default or current law CF updates were determined largely by an expenditure target formula. In 2015, the Medicare Access and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Reauthorization Act (MACRA) of 2015 permanently eliminated the existing expenditure target, ie, the sustainable growth rate (SGR), and replaced it with fixed updates that are specified in the legislation.

With the Medicare Conversion Factor decreasing by 9.9% over the years and inflation-adjusted payments to physicians effectively decreasing by 42%, the financial landscape for physicians remains challenging. The future demands vision, adaptability, and a keen understanding of both policy and market dynamics.

Good to Great by Jim Collins

In Good to Great, Jim Collins articulates a management methodology that’s based on a process of buildup followed by breakthrough. This can be broken into three broad stages, each driven by three key concepts:

- Disciplined people – Level 5 leadership, and “first who . . . then what”

- Disciplined thought–Confrontation of the brutal facts(yet without losing faith) and the “hedgehog” concept (simplicity within the “three circles”)

- Disciplined action–A culture of discipline and technology accelerators

Wrapping around this entire framework is a concept of “fly-wheel”—which, under disciplined people, thought, and action accumulates inertia and takes the company from good to great.

One concept in the Good to Great methodology is called The Stockdale Paradox. It’s named after Admiral Jim Stockdale, who was imprisoned in Vietnam and repeatedly tortured for over eight years. In a conversation with Collins, Stockdale described how he survived while so many died after just months in captivity:

“I never lost faith in the end of the story. I never doubted not only that I would get out, but also that I would prevail in the end and turn the experience into the defining event of my life, which, in retrospect, I would not trade.”

“Who didn’t make it out?” asked Collins.

“The optimists,” replied Stockdale. “They were the ones who said, ‘we’re going to be out by Christmas.’ And Christmas would come, and Christmas would go. Then they’d say, ‘We’re going to be out by Easter.’ And Easter would come, and Easter would go. And then Thanksgiving, and then it would be Christmas again. Then they died of a broken heart.

“You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end—which you can never afford to lose—with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be,” says Stockdale.(Puri, 2015)

Holding those two seemingly contradictory notions in his head simultaneously was the key to Stockdale survival. And it’s a perfect summary of the mindset you need to manage your office billing. You have to believe that you’ll be paid for your work. But you can never let your belief cloud your perception of reality: the payments to providers are costs for payers, whose objective is to improve profitability for their shareholders and, therefore, to reduce their payments to providers.

Claims are not paid by waiting for the payers to pay them. Claims are paid by payers who discover that delay and underpayment are more expensive than payment in full and on time (see Chapter 3). Without a system to make the payers pay, you’ll default to the payer’s system and find yourself giving up control.

Role of ClinicMind

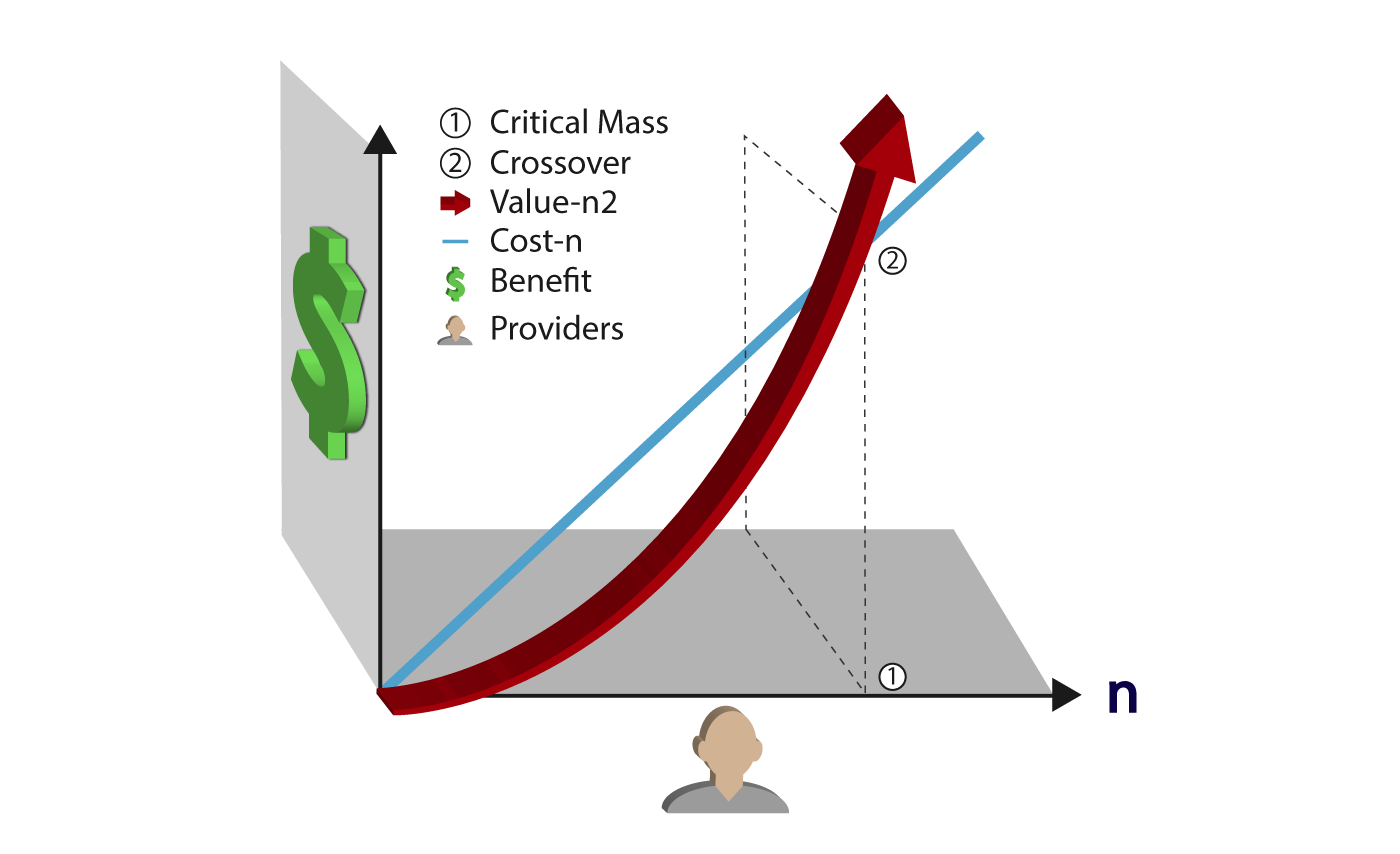

ClinicMind is a system that can help make the payers pay—and it leverages the “network effect” to amplify its value. The network effect, according to Wikipedia, “causes a good or service to have a value to a potential customer which depends on the number of other customers who own the good or are users of the service.”(Wikipedia contributors, 2023b)

One consequence of a network effect is that the purchase of a service by one individual in- directly benefits others who also use the same service. For example, by purchasing a telephone, a person makes other telephones more useful. The resulting bandwagon effect is a positive feedback loop.

For ClicniMind, the network effect (also known as Metcalfe’s law) says that while ClinicMind’s costs are proportional to the number of submitted claims, the value of ClinicMind is proportional to the square of the number of practice owners using it. For example, if you multiply the number of ClinicMind users by 10, your systemwide cost goes up by a factor of 10, but the value goes up a hundredfold. In other words, Metcalfe’s law, as applied to ClinicMind, says that the value of ClinicMind to the individual practice owner is proportional to the number, n, of other practice owners who share the same billing knowledge base and processes. Now, multiply this value by the number of practice owners, and you have a value for the whole operation that’s roughly proportional to n2 .

In the early 1980s, when Robert Metcalfe discovered his law, he was vague about “value.” In those days, it had something to do with sharing expensive resources (like fax machines and printers), exchanging electronic mail, and accessing communications technologies (such as the Internet).The network effect offers several distinct advantages for physicians and their practices:

- better reimbursement rates because of improved contract negotiation with payers,

- improved collections because of better billing performance achieved by sharing a knowledge base across the network, collective insights, best practices, and strategies, leading to improved billing performance and reduced errors.

- lower audit risk because of fewer billing errors

- efficient practice management,

- accumulating purchasing economies: As practices come together, they can leverage their combined purchasing power to achieve cost savings. This can lead to reduced rates on essential expenses such as malpractice insurance and group healthcare costs.

- added revenue sources from integrated applications.

And according to Metcalfe’s law, this value continues to grow, in step with each newly joined practice, long after you started using ClinicMind’s system.

The billing network allows the providers to consolidate their processing volumes and resources, matching the payer’s billing processing performance and controlling the billing process.

Conclusion:

The intricate dynamics of the healthcare industry, from the challenges of team cohesion during adversity to the complexities of payer-provider negotiations, underscore the importance of strategic management and informed decision-making. The story of Ernest Shackleton’s Antarctic expedition serves as a poignant reminder of the power of leadership and the necessity of mitigating negative influences.

Similarly, the contrasting landscapes of Medicare and private payers highlight the need for healthcare providers to be well-versed in their negotiations and understand the intricacies of their contracts. The emergence of payment models and the associated risks and rewards further complicate this landscape. Amidst these challenges, the power of the network effect, as demonstrated by ClinicMind, offers a beacon of hope.

By leveraging collective knowledge and shared resources, providers can amplify their negotiating power, streamline their operations, and ultimately deliver better patient care. As the healthcare landscape continues to evolve, staying informed, being proactive, and harnessing the power of networks will be paramount for success.

Resources:

- Babcock, B. (2021, February 16). How Your Independent Practice Can Better Negotiate with Payers. https://www.r1rcm.com/news/how-to-better-negotiate-with-payers

- How much more than Medicare do private insurers pay? A review of the literature | KFF. (2020, May 1). KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/how-much-more-than-medicare-do-private-insurers-pay-a-review-of-the-literature/

- Edmiston, Kelly D. (2022). Alternative Payment Models, Value-Based Payments, and Health Disparities. Center for Insurance Policy & Research Report. National Association of Insurance Commissioners.

- Quinn, K. (2015, August 18). The 8 Basic Payment Methods in Health Care. Annals of Internal Medicine. https://doi.org/10.7326/m14-2784

- Puri, A. (2015). Good to Great by Jim Collins. www.academia.edu. https://www.academia.edu/17471551/Good_to_Great_by_Jim_Collins

- Wikipedia contributors. (2023b). Network effect. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Network_effect#

- American Medical Association & American Medical Association. (2022, March 21). How value-based care is making payor contracts even more complex. American Medical Association. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/private-practices/how-value-based-care-making-payor-contracts-even-more-complex

- Frakt, A., & Frakt, A. (2014, January 8). Physician services spending: Medicare vs. private insurers | The Incidental Economist. The Incidental Economist. https://theincidentaleconomist.com/wordpress/physician-services-spending-medicare-vs-private-insurers/

A Future Book Publication Note:

This article is a chapter in the forthcoming 2nd Edition book “Medical Billing Networks and Processes,” authored by Dr. Yuval Lirov and planned for publication in 2024. We will post more chapters on this blog soon.